Long-lived credentials continue to be a risk

Long-lived credentials—i.e., those that are static and do not expire—are well-known as a major cause of cloud security breaches, and they continue to be a widespread issue in cloud environments. These types of credentials are widely regarded as insecure, not only because they never expire but also because they can easily be leaked in source code, container images, or configuration files. Indeed, leaks of long-lived credentials are one of the most common causes for security breaches in the cloud.

Despite common knowledge of this attack vector, we identified that organizations still have room to improve in replacing long-lived credentials with more secure solutions that use centralized identity management and short-lived credentials. We analyzed usage of long-lived credentials across AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud and found common trends across accounts in all three platforms. In AWS, 76 percent of IAM users have active access keys. In Azure AD, 50 percent of applications have active credentials, while 27 percent of Google Cloud service accounts have active access keys. The lower number for Google Cloud is likely due to the presence of service accounts created and managed by Google, which developers typically do not use for other purposes.

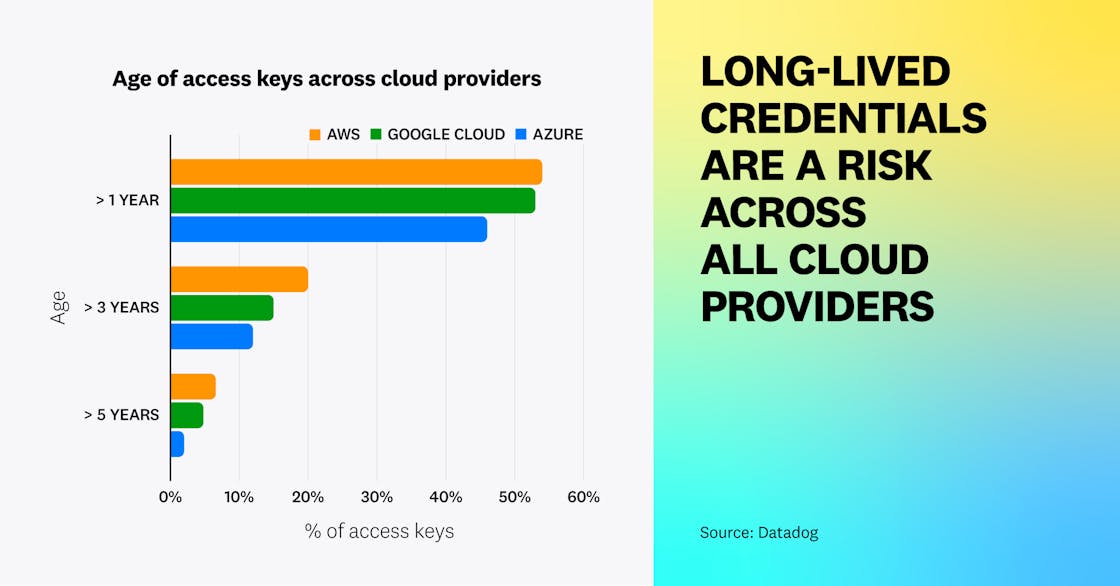

Across AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud, roughly half of access keys are more than 1 year old, and more than one in 10 are older than 3 years old. This demonstrates that access keys tend to live for longer than they should.

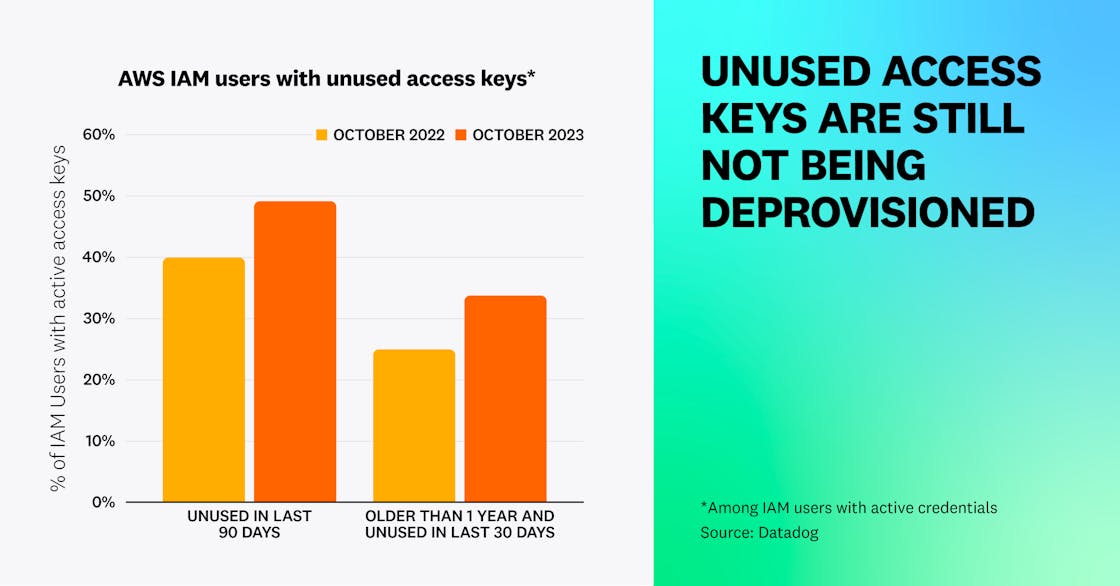

For AWS, we were able to compare these figures with historical data that we compiled for our 2022 report. Since that time, the situation with AWS credentials has unfortunately not improved. Many of the 76 percent of IAM users that have access keys—up from 72 percent from one year ago—do not actively use them. Among these users:

- Nearly half (49 percent) have an access key that has not been used in the past 90 days, up from 40 percent a year ago.

- One in three have active credentials that are older than 1 year and have not been used in the past 30 days, up from 25 percent a year ago.

It’s generally recommended to avoid long-lived credentials, both for humans and workloads, and instead to use identity federation and platform authentication. For AWS, this means using IAM Identity Center (formerly AWS SSO) federated with a central identity provider and avoiding IAM users. On Google Cloud, service accounts should not have access keys, and organizations should instead use secure authentication mechanisms that create time-bound credentials, such as service account impersonation, instance roles, or workload identity. In Azure, organizations should avoid the use of Azure AD application credentials when possible and instead opt for managed identities and workload identity.

“Long-lived credentials can be avoided in almost all use cases in the cloud in 2023. It’s great to see cloud providers make federation available in a growing number of scenarios. Additionally, one of the biggest benefits of temporary credentials is support for rich attribution. Actions performed in the cloud can be attributed to specific runs of CI jobs or instances of an auto-scaled application. This can be invaluable for troubleshooting, not just security. Their time-limited nature also makes attribution of compromise easier—one needs only query several hours of logs, rather than potentially months or years.”

Senior Engineer and AWS Serverless Hero

MFA for cloud access is not sufficiently enforced

Unlike on-premise environments, cloud providers’ administrative interfaces are APIs that are, by design, exposed to the internet. This is why, in the cloud, identity is the new perimeter—and securing identities is of paramount importance. Using and enforcing MFA is one of the most basic and effective steps in that effort. Data from both Microsoft and Google indicates that usage of MFA can prevent the vast majority of account takeovers. MFA can be enforced at the account or tenant level, and organizations should consider its use—particularly phishing-resistant methods such as FIDO2 security keys—as an essential part of a healthy cloud security posture.

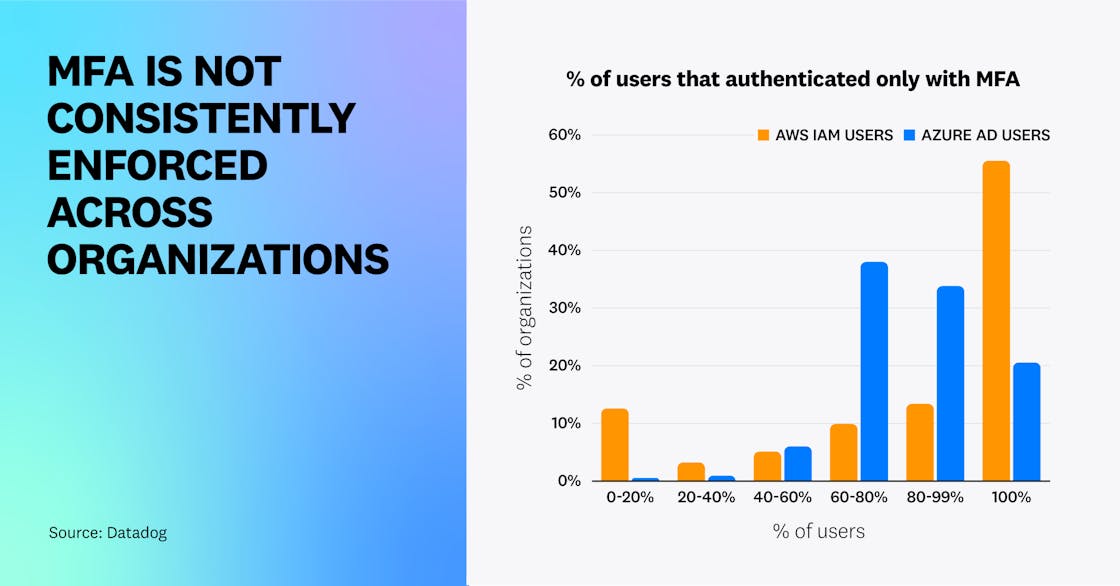

In our research, we analyzed MFA usage in AWS and Azure AD—reliably reporting on MFA usage in Google Cloud is not feasible at this time due to some limitations of Google Workspace Audit logs (e.g., logins using passkeys do not appear as MFA events). For each organization, we analyzed the percentage of its users that had successfully authenticated without MFA in October 2023.

In AWS, we identified that nearly a third (31 percent) of IAM users with console access have no MFA enforced, affecting two out of five organizations. We also found that 45 percent of AWS organizations had one or more IAM users authenticate to the AWS console without using MFA, and only 20 percent of Azure organizations had all Azure AD users authenticate with MFA.

These findings illustrate that, while industry statistics suggest MFA adoption is increasing, a substantial portion of organizations are not proactively enforcing it, leaving them at increased risk of credential theft or password-stuffing attacks.

In AWS, it’s recommended to avoid using IAM users and instead rely on a third-party identity provider that allows MFA to be enforced. If you do use IAM users in AWS, you can enforce MFA through the use of the aws:MultiFactorAuthPresent condition key. In Azure AD, MFA should typically be made mandatory by using a conditional access policy and ensuring that legacy authentication is disabled. In Google Workspace, MFA can be enforced at the organization or organization unit level.

In AWS, IMDSv2 is still widely unenforced, but adoption is rising

In AWS, enforcing the Instance Metadata Service V2 (IMDSv2) is critical to protect against server-side request forgery (SSRF) attacks, one of the most common ways attackers steal and abuse cloud credentials. IMDSv2 enforces the presence of additional HTTP headers, making it much harder for attackers to steal credentials from an EC2 instance.

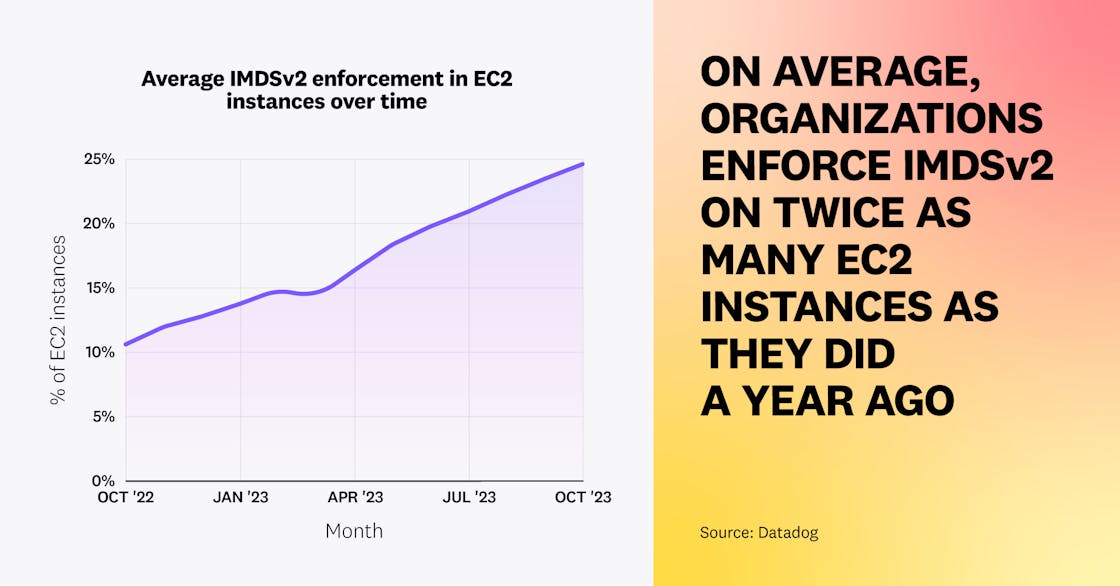

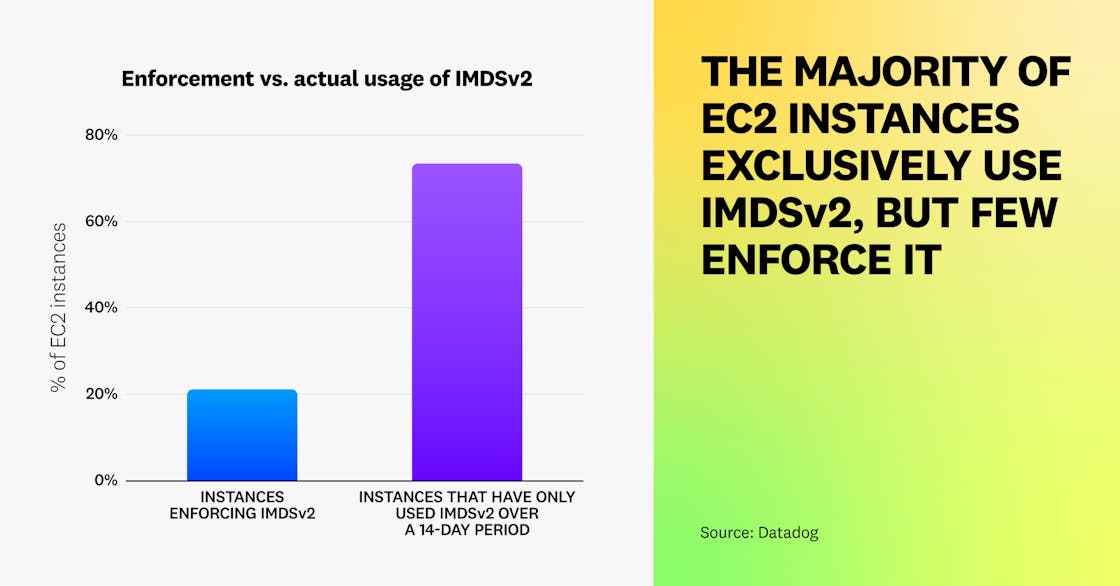

Although IMDSv2 was released in 2019, our 2022 study shows that, at the time, only 7 percent of EC2 instances were enforcing the usage of IMDSv2. Today, 21 percent of EC2 instances enforce IMDSv2. Organizations enforce IMDSv2 on 25 percent of their EC2 instances on average, up from 11 percent in September 2022. Although current adoption is still insufficient, we’re glad that organizations are starting to increase enforcement of IMDSv2.

However, enforcement varies based on age of deployment. Just 13 percent of EC2 instances older than one year enforce IMDSv2, compared to 31 percent of instances launched in the past several weeks. This reinforces that organizations are increasingly aware of IMDSv2, and that shorter-lived EC2 instances that are designed to be easily taken down or re-deployed benefit more from recent security improvements.

When an instance is insecurely configured and does not enforce IMDSv2, it’s still possible to use it—although an attacker would likely opt to use the insecure IMDSv1. We identified that nearly three out of four EC2 instances (73 percent) had only used IMDSv2 over the 14-day period between October 12 and October 26, showing the disconnect between what’s enforced and what’s actually used. In fact, this means that the vast majority of EC2 instances could enforce IMDSv2 without any functional impact or disruption. It’s recommended to enforce IMDSv2 on all your EC2 instances. (See also AWS’ own guide.)

You can enforce IMDSv2 on your instances through the use of service control policies (SCPs). AWS has also recently released a setting at the Amazon Machine Instance (AMI) level that enforces IMDSv2 by default for all EC2 instances launched from that AMI. Finally, the AWS documentation features a dedicated guide about transitioning to IMDSv2.

“Seeing improvement in IMDSv2 enforcement in 2023 likely shows that the most impactful change has been AWS implementing more secure defaults within its AMIs and Compute services. Many companies are also recognizing the critical importance of enforcing IMDSv2 usage on the internet edges of their environments. However, there is a long road ahead, as SSRF and proxy attacks are still largely obscure concepts unknown to many builders in the cloud. Cloud providers are starting to provide more detailed warnings and click-through advisory notices when permitting less secure options in some services. Compute services and, in particular, IMDS are worthy of such warnings. Additionally, feedback and pressure should continue to be placed on commercial products that do not support IMDSv2.”

Senior Security Engineering Manager, Cloud Security at Robinhood

Adoption of public access blocks in cloud storage services is increasing

Public cloud storage buckets are now a well-understood source of data leakage in cloud environments. Attackers stealing sensitive data from cloud storage have been documented countless times, including in 2023. These breaches are often due to the complexity of securely configuring storage buckets, and although buckets are private by default, there are many mechanisms by which they can inadvertently be made publicly available. In addition, some storage buckets were created a long time ago—for instance, Amazon S3 was publicly released in 2006, more than 17 years ago—before some modern safeguards were commonplace.

Today, cloud providers implement mechanisms to proactively block public access to cloud storage, even on misconfigured buckets, and prevent buckets from becoming publicly available by mistake. These allow practitioners to secure a whole AWS account, Azure storage account, or Google Cloud project at once and ensure that human error doesn’t turn into a data breach. (Note that we did not include Google Cloud Storage in our analysis, because public access in Google Cloud is typically blocked at the project, folder, or organization level through an organization policy constraint.)

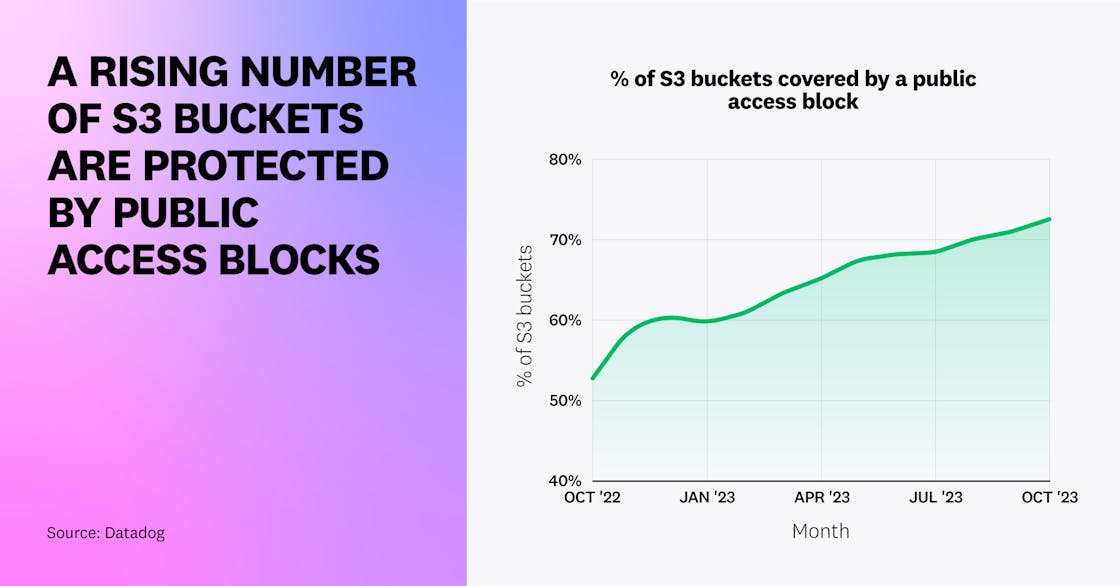

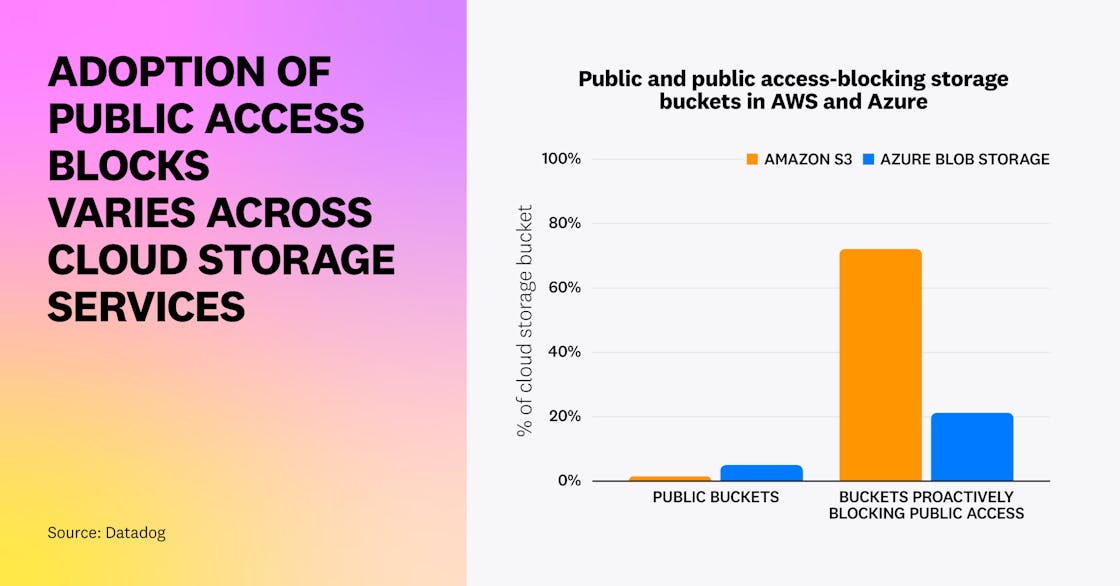

On AWS, we identified that nearly three-quarters (72 percent) of S3 buckets are covered by a public S3 access block, either at the bucket or account level, up from half (52 percent) in October 2022. This shows that organizations are increasingly aware of this mechanism, introduced in 2018.

On Azure, two out of five blob storage containers (21 percent) are in a storage account that proactively blocks public access, making sure that any dangerously configured blob storage it contains is not effectively made public.

Overall, a small portion (1.5 percent) of Amazon S3 buckets are public (i.e., they have a public bucket policy and are not covered by a public access block at the account or bucket level). Similarly, a small number of Azure storage blob containers (5 percent) are publicly accessible and in a storage account not blocking public access. While these buckets don’t necessarily contain sensitive data, they could inadvertently become repositories for sensitive information in the future.

We believe that more organizations proactively block S3 public access due to wider awareness of this practice, the high number of documented security breaches related to public access, and because AWS introduced the S3 public access block in 2018. Microsoft also released the equivalent Azure feature in 2020. In addition, since April 2023, AWS has been blocking public access by default on all buckets, which is not the case for Azure—although it’s also planned in the near future. Organizations should continue to audit the configuration of their storage buckets and ensure public access blocks are enforced, except in specific use cases where public access is warranted or necessary. In many such cases, leveraging a content distribution network (CDN) service such as Amazon CloudFront or Azure CDN is more performant, cost-effective, and secure than exposing buckets directly.

A substantial portion of cloud workloads are excessively privileged

In cloud environments, configuring permissions can be a tedious task that often leads to workloads having more privileges than needed. Often, a seemingly innocuous set of permissions could allow an attacker to escalate their privileges. While full administrator access is relatively simple to identify, “shadow administrator” permissions—which allow an identity to indirectly escalate their privileges and access sensitive data—are typically harder to spot.

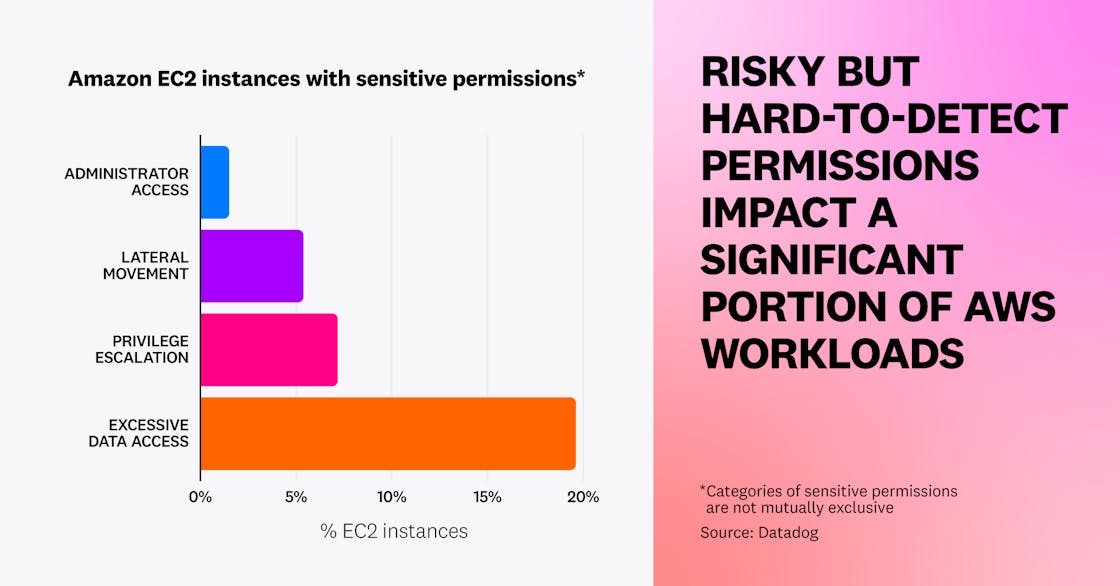

In AWS, only a small number (1.5 percent) of Amazon EC2 instances have full administrator privileges. An attacker compromising such an instance—for example, by exploiting a web application that runs on it—would be able to obtain the credentials made available via the instance metadata service and thereby access sensitive data in the account.

But this figure doesn’t tell the full story. An attacker does not need full administrator privileges to have a substantial impact—there are other, more common and challenging-to-uncover types of permissions they can leverage. We found that:

- 5.4 percent of EC2 instances have risky permissions that allow lateral movement in the account, such as connecting to other instances using SSM Sessions Manager.

- 7.2 percent allow an attacker to gain full administrative access to the account by privilege escalation, such as permissions to create a new IAM user with administrator privileges.

- 20 percent have excessive data access, such as listing and accessing data from all S3 buckets in the account.

(Note that these conditions are not mutually exclusive—a specific instance can fall into several of these categories.)

Overall, nearly one in four EC2 instances (23 percent) have administrator or highly sensitive permissions to the AWS account they run in.

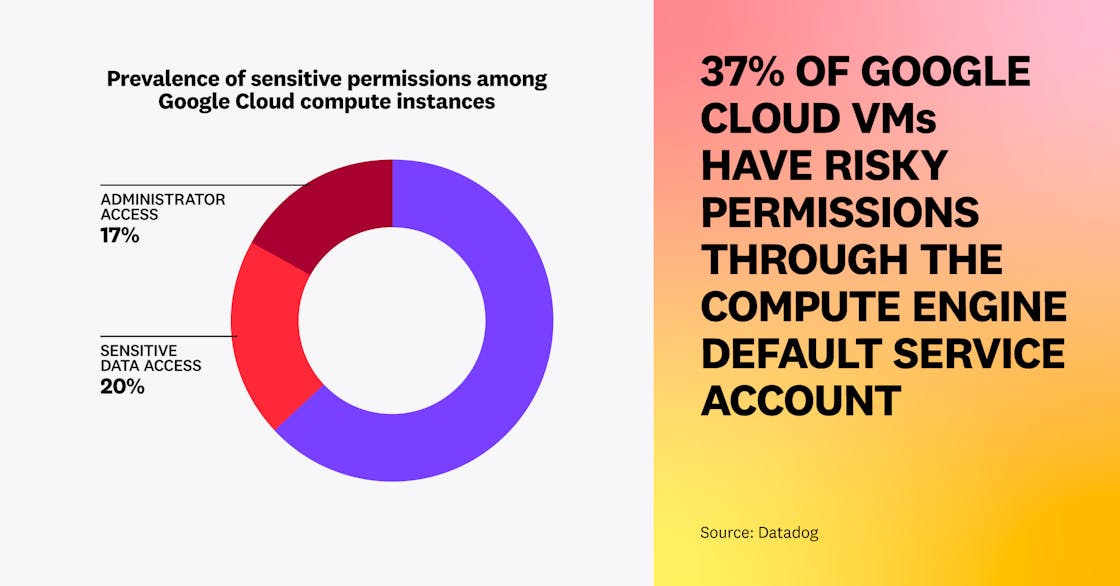

On Google Cloud, 20 percent of virtual machines (VMs) have privileged “editor” permissions on the project they run in, through the use of the default compute service account with the unrestricted cloud-platform scope. In addition, 17 percent have full read access to Google Cloud Storage (GCS) buckets and BigQuery datasets through the same mechanism—so in total, more than one in three Google Cloud VMs (37 percent) have sensitive permissions to a project.

Organizations using Google Cloud should enable the “Disable automatic IAM grants for default service accounts” organization policy and ensure that virtual machines use a non-default service account.

Managing IAM permissions of cloud workloads is not an easy task. Administrator access is not the only risk to monitor—it’s critical to also be wary of sensitive permissions that allow a user to access sensitive data or escalate privileges. Because cloud workloads are a common entry point for attackers, it’s critical to ensure permissions on these resources are as limited as possible.

“Insecure default configurations from cloud providers optimize for the ease of initial adoption, but they are often at odds with the level of hardening required for most production deployments. Initial configurations such as over-privileged IAM roles and permissive firewall rules tend to have inertia—once deployed and working, they are more challenging to lock down after the fact. Therefore, the discipline of hardening the security of initial configurations early in the deployment lifecycle is a key virtue of a mature cloud-native organization's culture.”

Staff Security Engineering, Ghost Security

Many virtual machines remain publicly exposed to the internet

Exposing virtual machines (VMs) to the public internet is a significant risk in cloud environments. Attackers frequently target exposed services by running brute-force attacks or exploiting known protocol-level vulnerabilities such as BlueKeep, which the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) still reports as one of the most commonly exploited vulnerabilities of 2022.

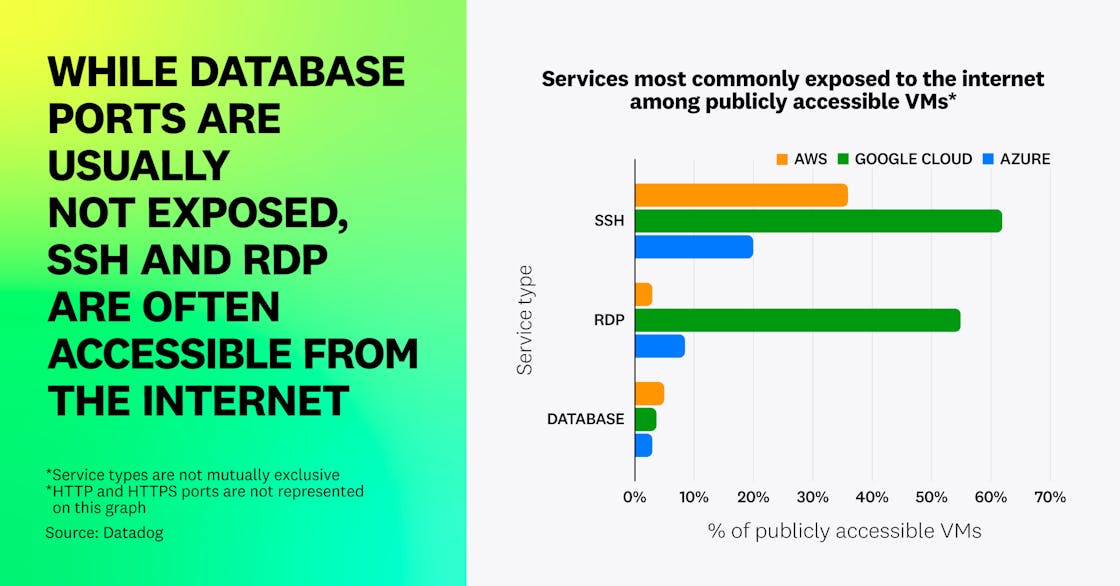

We identified that 7 percent of EC2 instances, 3 percent of Azure VMs, and 13 percent of Google Cloud VMs are publicly exposed to the internet—i.e., they have at least one port allowing traffic from the internet.

Among instances that are publicly exposed, HTTP and HTTPS are the most commonly exposed ports, and are not considered risky in general. After these, SSH and RDP remote access protocols are common. The most commonly exposed database technologies are MongoDB, Redis, MSSQL, and Elasticsearch.

We hypothesize that the higher public exposure and strong prevalence of open SSH and RDP ports in Google Cloud is due to the fact that default pre-populated firewall rules in the default network allow SSH and RDP from the internet. While developers can disable provisioning of this network for new projects through the “skip default network creation” organization policy constraint, it does not apply to existing projects. The resulting differences in percentage of internet-exposed VMs show once again the practical impact that insecure defaults can have on organizations’ security posture.

Across all cloud platforms, organizations should avoid exposing VMs to the public internet and instead use IAM-based secure access mechanisms such as AWS SSM Sessions Manager, Amazon EC2 Instance Connect, Google Cloud Identity-Aware Proxy (IAP), Google Cloud OS Login, or Azure Bastion. This especially applies to database systems running on VMs, since databases typically contain sensitive data and are straightforward for attackers to discover—for instance, through passive network scanning search engines like Shodan or Censys. Databases should be kept on internal networks and accessed through one of the mechanisms previously mentioned.